The Nightingale

Hans Christian Andersen

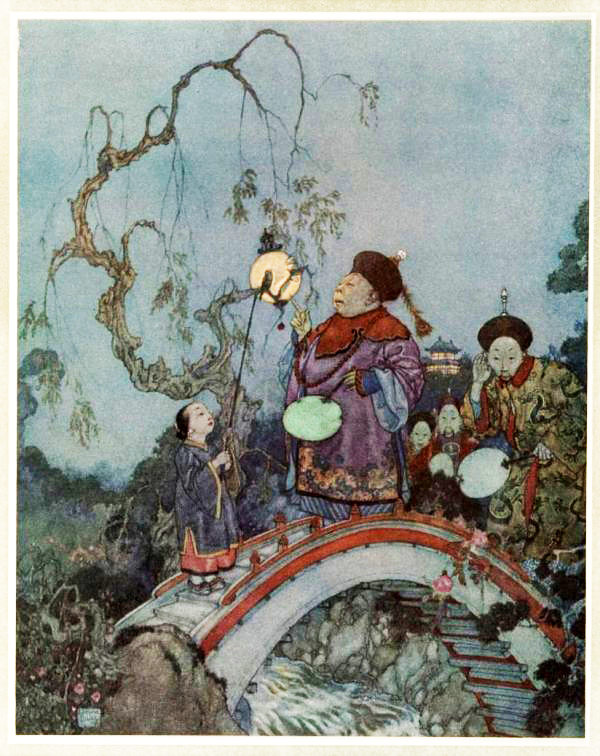

In China, as you know, the Emperor is a Chinaman, and all the people around him are Chinamen too. It is many years since the story I am going to tell you happened, but that is all the more reason for telling it, lest it should be forgotten. The emperor’s palace was the most beautiful thing in the world; it was made entirely of the finest porcelain, very costly, but at the same time so fragile that it could only be touched with the very greatest care. There were the most extraordinary flowers to be seen in the garden; the most beautiful ones had little silver bells tied to them, which tinkled perpetually, so that one should not pass the flowers without looking at them. Every little detail in the garden had been most carefully thought out, and it was so big, that even the gardener himself did not know where it ended. If one went on walking, one came to beautiful woods with lofty trees and deep lakes. The wood extended to the sea, which was deep and blue, deep enough for large ships to sail up right under the branches of the trees. Among these trees lived a nightingale, which sang so deliciously, that even the poor fisherman, who had plenty of other things to do, lay still to listen to it, when he was out at night drawing in his nets. ‘Heavens, how beautiful it is!’ he said, but then he had to attend to his business and forgot it. The next night when he heard it again he would again exclaim, ‘Heavens, how beautiful it is!’

Travellers came to the emperor’s capital, from every country in the world; they admired everything very much, especially the palace and the gardens, but when they heard the nightingale they all said, ‘This is better than anything!’

When they got home they described it, and the learned ones wrote many books about the town, the palace and the garden; but nobody forgot the nightingale, it was always put above everything else. Those among them who were poets wrote the most beautiful poems, all about the nightingale in the woods by the deep blue sea. These books went all over the world, and in course of time some of them reached the emperor. He sat in his golden chair reading and reading, and nodding his head, well pleased to hear such beautiful descriptions of the town, the palace and the garden. ‘But the nightingale is the best of all,’ he read.

‘What is this?’ said the emperor. ‘The nightingale? Why, I know nothing about it. Is there such a bird in my kingdom, and in my own garden into the bargain, and I have never heard of it? Imagine my having to discover this from a book?’

Then he called his gentleman-in-waiting, who was so grand that when any one of a lower rank dared to speak to him, or to ask him a question, he would only answer ‘P,’ which means nothing at all.

‘There is said to be a very wonderful bird called a nightingale here,’ said the emperor. ‘They say that it is better than anything else in all my great kingdom! Why have I never been told anything about it?’

‘I have never heard it mentioned,’ said the gentleman-in-waiting. ‘It has never been presented at court.’

‘I wish it to appear here this evening to sing to me,’ said the emperor. ‘The whole world knows what I am possessed of, and I know nothing about it!’

‘I have never heard it mentioned before,’ said the gentleman-in-waiting. ‘I will seek it, and I will find it!’

But where was it to be found? The gentleman-in-waiting ran upstairs and downstairs and in and out of all the rooms and corridors. No one of all those he met had ever heard anything about the nightingale; so the gentleman-in-waiting ran back to the emperor, and said that it must be a myth, invented by the writers of the books. ‘Your imperial majesty must not believe everything that is written; books are often mere inventions, even if they do not belong to what we call the black art!’

‘But the book in which I read it is sent to me by the powerful Emperor of Japan, so it can’t be untrue. I will hear this nightingale; I insist upon its being here tonight. I extend my most gracious protection to it, and if it is not forthcoming, I will have the whole court trampled upon after supper!’

‘Tsing-pe!’ said the gentleman-in-waiting, and away he ran again, up and down all the stairs, in and out of all the rooms and corridors; half the court ran with him, for they none of them wished to be trampled on. There was much questioning about this nightingale, which was known to all the outside world, but to no one at court.

At last they found a poor little maid in the kitchen. She said, ‘Oh heavens, the nightingale? I know it very well. Yes, indeed it can sing. Every evening I am allowed to take broken meat to my poor sick mother: she lives down by the shore. On my way back, when I am tired, I rest awhile in the wood, and then I hear the nightingale. Its song brings the tears into my eyes; I feel as if my mother were kissing me!’

‘Little kitchen-maid,’ said the gentleman-in-waiting, ‘I will procure you a permanent position in the kitchen, and permission to see the emperor dining, if you will take us to the nightingale. It is commanded to appear at court to-night.’

Then they all went out into the wood where the nightingale usually sang. Half the court was there. As they were going along at their best pace a cow began to bellow.

‘Oh!’ said a young courtier, ‘there we have it. What wonderful power for such a little creature; I have certainly heard it before.’

‘No, those are the cows bellowing; we are a long way yet from the place.’ Then the frogs began to croak in the marsh.

‘Beautiful!’ said the Chinese chaplain, ‘it is just like the tinkling of church bells.’

‘No, those are the frogs!’ said the little kitchen-maid. ‘But I think we shall soon hear it now!’

Then the nightingale began to sing.

‘There it is!’ said the little girl. ‘Listen, listen, there it sits!’ and she pointed to a little grey bird up among the branches.

‘Is it possible?’ said the gentleman-in-waiting. ‘I should never have thought it was like that. How common it looks! Seeing so many grand people must have frightened all its colours away.’

‘Little nightingale!’ called the kitchen-maid quite loud, ‘our gracious emperor wishes you to sing to him!’

‘With the greatest of pleasure!’ said the nightingale, warbling away in the most delightful fashion.

‘It is just like crystal bells,’ said the gentleman-in-waiting. ‘Look at its little throat, how active it is. It is extraordinary that we have never heard it before! I am sure it will be a great success at court!’

‘Shall I sing again to the emperor?’ said the nightingale, who thought he was present.

‘My precious little nightingale,’ said the gentleman-in-waiting, ‘I have the honour to command your attendance at a court festival to-night, where you will charm his gracious majesty the emperor with your fascinating singing.’

‘It sounds best among the trees,’ said the nightingale, but it went with them willingly when it heard that the emperor wished it.

The palace had been brightened up for the occasion. The walls and the floors, which were all of china, shone by the light of many thousand golden lamps. The most beautiful flowers, all of the tinkling kind, were arranged in the corridors; there was hurrying to and fro, and a great draught, but this was just what made the bells ring; one’s ears were full of the tinkling. In the middle of the large reception-room where the emperor sat a golden rod had been fixed, on which the nightingale was to perch. The whole court was assembled, and the little kitchen-maid had been permitted to stand behind the door, as she now had the actual title of cook. They were all dressed in their best; everybody’s eyes were turned towards the little grey bird at which the emperor was nodding.

The nightingale sang delightfully, and the tears came into the emperor’s eyes, nay, they rolled down his cheeks; and then the nightingale sang more beautifully than ever, its notes touched all hearts. The emperor was charmed, and said the nightingale should have his gold slipper to wear round its neck. But the nightingale declined with thanks; it had already been sufficiently rewarded. ‘I have seen tears in the eyes of the emperor; that is my richest reward. The tears of an emperor have a wonderful power! God knows I am sufficiently recompensed!’ and then it again burst into its sweet heavenly song.

‘That is the most delightful coquetting I have ever seen!’ said the ladies, and they took some water into their mouths to try and make the same gurgling when any one spoke to them, thinking so to equal the nightingale. Even the lackeys and the chambermaids announced that they were satisfied, and that is saying a great deal; they are always the most difficult people to please.

Yes, indeed, the nightingale had made a sensation. It was to stay at court now, and to have its own cage, as well as liberty to walk out twice a day, and once in the night. It always had twelve footmen, with each one holding a ribbon which was tied round its leg. There was not much pleasure in an outing of that sort.

The whole town talked about the marvellous bird, and if two people met, one said to the other ‘Night,’ and the other answered ‘Gale,’ and then they sighed, perfectly understanding each other. Eleven cheesemongers’ children were called after it, but they had not got a voice among them.

One day a large parcel came for the emperor; outside was written the word ‘Nightingale.’

‘Here we have another new book about this celebrated bird,’ said the emperor. But it was no book; it was a little work of art in a box, an artificial nightingale, exactly like the living one, but it was studded all over with diamonds, rubies and sapphires. When the bird was wound up it could sing one of the songs the real one sang, and it wagged its tail, which glittered with silver and gold. A ribbon was tied round its neck on which was written, ‘The Emperor of Japan’s nightingale is very poor compared to the Emperor of China’s.’

Everybody said, ‘Oh, how beautiful!’ And the person who brought the artificial bird immediately received the title of Imperial Nightingale-Carrier in Chief.

‘Now, they must sing together; what a duet that will be.’

Then they had to sing together, but they did not get on very well, for the real nightingale sang in its own way, and the artificial one could only sing waltzes.

‘There is no fault in that,’ said the music-master; ‘it is perfectly in time and correct in every way!’

Then the artificial bird had to sing alone. It was just as great a success as the real one, and then it was so much prettier to look at; it glittered like bracelets and breast-pins. It sang the same tune three and thirty times over, and yet it was not tired; people would willingly have heard it from the beginning again, but the emperor said that the real one must have a turn now–but where was it? No one had noticed that it had flown out of the open window, back to its own green woods.

‘But what is the meaning of this?’ said the emperor.

All the courtiers railed at it, and said it was a most ungrateful bird.

‘We have got the best bird though,’ said they, and then the artificial bird had to sing again, and this was the thirty-fourth time that they heard the same tune, but they did not know it thoroughly even yet, because it was so difficult.

The music-master praised the bird tremendously, and insisted that it was much better than the real nightingale, not only as regarded the outside with all the diamonds, but the inside too. ‘Because you see, my ladies and gentlemen, and the emperor before all, in the real nightingale you never know what you will hear, but in the artificial one everything is decided beforehand! So it is, and so it must remain, it can’t be otherwise. You can account for things, you can open it and show the human ingenuity in arranging the waltzes, how they go, and how one note follows upon another!’

‘Those are exactly my opinions,’ they all said, and the music-master got leave to show the bird to the public next Sunday. They were also to hear it sing, said the emperor. So they heard it, and all became as enthusiastic over it as if they had drunk themselves merry on tea, because that is a thoroughly Chinese habit. Then they all said ‘Oh,’ and stuck their forefingers in the air and nodded their heads; but the poor fishermen who had heard the real nightingale said, ‘It sounds very nice, and it is very like the real one, but there is something wanting, we don’t know what.’

The real nightingale was banished from the kingdom. The artificial bird had its place on a silken cushion, close to the emperor’s bed: all the presents it had received of gold and precious jewels were scattered round it. Its title had risen to be ‘Chief Imperial Singer of the Bed-Chamber,’ in rank number one, on the left side; for the emperor reckoned that side the important one, where the heart was seated. And even an emperor’s heart is on the left side.

The music-master wrote five-and-twenty volumes about the artificial bird; the treatise was very long and written in all the most difficult Chinese characters. Everybody said they had read and understood it, for otherwise they would have been reckoned stupid, and then their bodies would have been trampled upon.

Things went on in this way for a whole year. The emperor, the court, and all the other Chinamen knew every little gurgle in the song of the artificial bird by heart; but they liked it all the better for this, and they could all join in the song themselves. Even the street boys sang ‘zizizi’ and ‘cluck, cluck, cluck,’ and the emperor sang it too.

But one evening when the bird was singing its best, and the emperor was lying in bed listening to it, something gave way inside the bird with a ‘whizz.’ Then a spring burst, ‘whirr’ went all the wheels, and the music stopped. The emperor jumped out of bed and sent for his private physicians, but what good could they do? Then they sent for the watchmaker, and after a good deal of talk and examination he got the works to go again somehow; but he said it would have to be saved as much as possible, because it was so worn out, and he could not renew the works so as to be sure of the tune. This was a great blow! They only dared to let the artificial bird sing once a year, and hardly that; but then the music-master made a little speech, using all the most difficult words. He said it was just as good as ever, and his saying it made it so.

Five years now passed, and then a great grief came upon the nation, for they were all very fond of their emperor, and he was ill and could not live, it was said. A new emperor was already chosen, and people stood about in the street, and asked the gentleman-in-waiting how their emperor was going on.

‘P,’ answered he, shaking his head.

The emperor lay pale and cold in his gorgeous bed, the courtiers thought he was dead, and they all went off to pay their respects to their new emperor. The lackeys ran off to talk matters over, and the chambermaids gave a great coffee-party. Cloth had been laid down in all the rooms and corridors so as to deaden the sound of footsteps, so it was very, very quiet. But the emperor was not dead yet. He lay stiff and pale in the gorgeous bed with its velvet hangings and heavy golden tassels. There was an open window high above him, and the moon streamed in upon the emperor, and the artificial bird beside him.

The poor emperor could hardly breathe, he seemed to have a weight on his chest, he opened his eyes, and then he saw that it was Death sitting upon his chest, wearing his golden crown. In one hand he held the emperor’s golden sword, and in the other his imperial banner. Round about, from among the folds of the velvet hangings peered many curious faces: some were hideous, others gentle and pleasant. They were all the emperor’s good and bad deeds, which now looked him in the face when Death was weighing him down.

‘Do you remember that?’ whispered one after the other; ‘Do you remember this?’ and they told him so many things that the perspiration poured down his face.

‘I never knew that,’ said the emperor. ‘Music, music, sound the great Chinese drums!’ he cried, ‘that I may not hear what they are saying.’ But they went on and on, and Death sat nodding his head, just like a Chinaman, at everything that was said.

‘Music, music!’ shrieked the emperor. ‘You precious little golden bird, sing, sing! I have loaded you with precious stones, and even hung my own golden slipper round your neck; sing, I tell you, sing!’

But the bird stood silent; there was nobody to wind it up, so of course it could not go. Death continued to fix the great empty sockets of his eyes upon him, and all was silent, so terribly silent.

Suddenly, close to the window, there was a burst of lovely song; it was the living nightingale, perched on a branch outside. It had heard of the emperor’s need, and had come to bring comfort and hope to him. As it sang the faces round became fainter and fainter, and the blood coursed with fresh vigour in the emperor’s veins and through his feeble limbs.

Even Death himself listened to the song and said, ‘Go on, little nightingale, go on!’

‘Yes, if you give me the gorgeous golden sword; yes, if you give me the imperial banner; yes, if you give me the emperor’s crown.’

And Death gave back each of these treasures for a song, and the nightingale went on singing. It sang about the quiet churchyard, when the roses bloom, where the elder flower scents the air, and where the fresh grass is ever moistened anew by the tears of the mourner. This song brought to Death a longing for his own garden, and, like a cold grey mist, he passed out of the window.

‘Thanks, thanks!’ said the emperor; ‘you heavenly little bird, I know you! I banished you from my kingdom, and yet you have charmed the evil visions away from my bed by your song, and even Death away from my heart! How can I ever repay you?’

‘You have rewarded me,’ said the nightingale. ‘I brought the tears to your eyes, the very first time I ever sang to you, and I shall never forget it! Those are the jewels which gladden the heart of a singer;–but sleep now, and wake up fresh and strong! I will sing to you!’

Then it sang again, and the emperor fell into a sweet refreshing sleep. The sun shone in at his window, when he woke refreshed and well; none of his attendants had yet come back to him, for they thought he was dead, but the nightingale still sat there singing.

‘You must always stay with me!’ said the emperor. ‘You shall only sing when you like, and I will break the artificial bird into a thousand pieces!’

‘Don’t do that!’ said the nightingale, ‘it did all the good it could! keep it as you have always done! I can’t build my nest and live in this palace, but let me come whenever I like, then I will sit on the branch in the evening, and sing to you. I will sing to cheer you and to make you thoughtful too; I will sing to you of the happy ones, and of those that suffer too. I will sing about the good and the evil, which are kept hidden from you. The little singing bird flies far and wide, to the poor fisherman, and the peasant’s home, to numbers who are far from you and your court. I love your heart more than your crown, and yet there is an odour of sanctity round the crown too!–I will come, and I will sing to you! But you must promise me one thing!’

‘Everything!’ said the emperor, who stood there in his imperial robes which he had just put on, and he held the sword heavy with gold upon his heart.

‘One thing I ask you! Tell no one that you have a little bird who tells you everything; it will be better so!’

Then the nightingale flew away. The attendants came in to see after their dead emperor, and there he stood, bidding them ‘Good morning!’

*This tale has been taken from: Stories from Hans Andersen, with Illustrations by Edmund Dulac; published by Hodder & Stoughton, London.

This work is in the public domain.